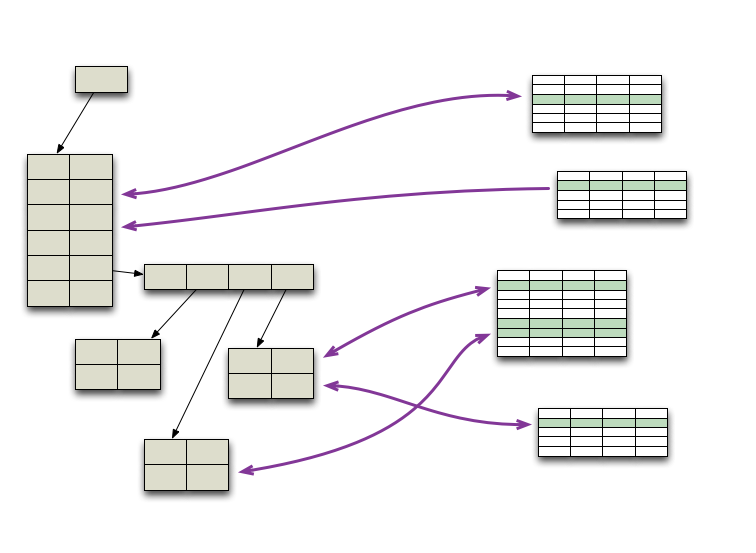

ORM is not ROM

Image credit: Martin Fowler https://martinfowler.com/bliki/OrmHate.html

ORM libraries provide mapping capabilities between relational data sitting in a RDBMS and objects interacting in memory. And like all developers tools, they are sometimes misused. When using an ORM we are supposed to map objects interactions to a relational model. Often we end up mapping a relational model using OOP syntax.

I tried to compile a short list of situations illustrating a miss-use or a non efficient use of ORM capabilities. Commonly referred to as anti-patterns. Certainly there are more out-here. I just list the ones I encountered the most often in code bases, and especially the anti-patterns that are common to most of the systems. For each situation, I propose a possible solution to make the code better.

In the following example we will suppose the worst case scenario. We have to map an existing database which is currently used by other systems. In short, we can’t change the database in any way.

Map bad column names to bad properties and accessors names

Naming things in software (besides being hard) can have a tremendous effect on code readability. By default, an ORM will map each database column to a property with the same or a curated name.

One example was a table that had 2 columns delivery and delivery1. After checking the existing records, it was clear that those columns actually contained delivery_type and delivery_fee informations. There is a popular misconception of trying to reflect the database in the mapping.

The following mapping is perfectly valid.

/**

* @ORM\Column(name="delivery", type="integer")

*/

private $deliveryType;

/**

* @ORM\Column(name="delivery1", type="integer")

*/

private $deliveryFee;

This small difference can have a big impact on the code readability. The following snippet could be hard to understand

if ($order->getDelivery() === 3) {

$order->setDelivery1($order->getDelivery1()+10);

}

After renaming (and a small improvement), it could be easier to understand

if ($order->getDeliveryType() === Delivery::COURIER) {

$order->setDeliveryFee($order->getDeliveryFee()+10);

}

The same technique applies to bad table names as well, an entity class name does not necessarily match the table name.

Map a nullable column to a nullable property

When a database column allows null as a value, it usually means the absence of a value.

As an example, consider an order table with a nullable column delivery_fee. A mapped entity would look like

class Order

{

/**

* @ORM\Column(type="integer", nullable="true")

*/

private $deliveryFee;

public function getDeliveryFee()

{

return $this->deliveryFee;

}

public function setDeliveryFee($deliveryFee)

{

$this->deliveryFee = $deliveryFee;

}

}

Now all the rest of the code will deal with two different data types: integer and null. This will manifest in the code as casts and ifs, like the following example:

function someCalculation(Order $order)

{

$this->total += (int)$order->getDeliveryFee();

}

function someController(Order $order, $deliveryFee)

{

if ($deliveryFee > 0) {

$order->setDeliveryFee($deliveryFee);

}

}

One solution is to map null values to a special value of the same data type, and perform the necessary casts and ifs within the mapped entity. The previous entity could be rewritten like this

class Order

{

/**

* @ORM\Column(type="integer", nullable="true")

*/

private $deliveryFee;

public function getDeliveryFee(): int

{

return (int)$this->deliveryFee;

}

public function setDeliveryFee(int $deliveryFee)

{

if ($deliveryFee === 0) {

$deliveryFee = null;

}

$this->deliveryFee = $deliveryFee;

}

}

Now the nullability of this column is contained within the entity. As a nice side effect, now we could type-hint the entity methods arguments and return types.

This transformation will result in a simpler calling code.

function someCalculation(Order $order)

{

$this->total += $order->getDeliveryFee();

}

function someController(Order $order, $deliveryFee)

{

$order->setDeliveryFee($deliveryFee);

}

Map an Enum column to property with getters and setters

Enum here doesn’t necessarily mean an SQL Enum type. But any column that contain a fixed set of possible values. The following mapping will work with any scalar type of the Order state column (omitted constants definition for brevity).

class Order

{

/**

* @ORM\Column(type="integer")

*/

private $state = self::STATE_NEW;

public function setState($state)

{

if (!in_array($state,

[self::STATE_NEW, self::STATE_CONFIRMED, self::STATE_CANCELED])

) {

throw new \InvalidArgumentException("Invalid state");

}

$this->state = $state;

}

public function getState()

{

return $this->state;

}

}

This example makes it hard to find out from where an order can be canceled, or which parts are interested in confirmed orders.

One solution to map Enum like columns, is to hide it behind a set of issers and actions.

We can rewrite the previous entity as following

class Order

{

/**

* @ORM\Column(type="integer")

*/

private $state = self::STATE_NEW;

public function confirm()

{

$this->state = self::STATE_CONFIRMED;

}

public function isConfirmed()

{

return $this->state === self::STATE_CONFIRMED;

}

public function cancel()

{

$this->state = self::STATE_CANCELED;

}

public function isCanceled()

{

return $this->state === self::STATE_CANCELED;

}

}

Starting from PHP7.1.0 we can even declare the constants as private to enforce encapsulation.

With this version, one could easily use the IDE’s Find Usages feature to quickly find who is interested in which status and who is doing what. You may need to handle all states in same parts of the code, fine, a generic getState method can be used there. But you should review your design first, most of the time you may find a routine that is doing many things.

This also enables more fine grained changes, we could enhance the cancel routine to

public function cancel()

{

if ($this->state === self::STATE_RETURNED) {

throw new \LogicException('Cannot cancel a returned order');

}

$this->state = self::STATE_CANCELED;

}

Such mapping will make code changes more contained and with less to no side effects. Which are major contributors to hidden bugs.

Map multipurpose columns to multipurpose properties

Sometimes when a system evolves in an unexpected way, it’s database and code base may do the same. This can result in a column holding different types of informations and often related.

In one example, a group by on a column named delivery returned the values

| delivery |

|---|

| store |

| courier |

| store_online |

| courier_online |

After looking up more data, it became clear the meaning of those values

| delivery | meaning |

|---|---|

| store | store delivery, cash on delivery |

| courier | courier delivery, cash on delivery |

| store_online | store delivery, paid online |

| courier_online | courier delivery, paid online |

We are obviously looking at delivery and payment informations mixed in this column. If we just use the auto-generated mapping, we would end up with a mapping like

class Order

{

/**

* @ORM\Column(type="string")

*/

private $delivery;

public function getDelivery()

{

return $this->delivery;

}

}

Such simplistic mapping would clutter the code with conditionals like

if (

$order->getDelivery() === Order::DELIVERY_COURIER

|| $order->getDelivery() === Order::DELIVERY_COURIER_ONLINE

) {

//hand to courier

} else {

//dispatch to shop

}

One possible approach is to expose this column as two sets of accessors, one for delivery type and one for payment type

class Order

{

/**

* @ORM\Column(type="string")

*/

private $delivery;

public function getDeliveryType()

{

if (

$this->delivery === self::DELIVERY_COURIER ||

$this->delivery === self::DELIVERY_COURIER_ONLINE

) {

return self::DELIVERY_TYPE_COURIER;

}

if (

$this->delivery === self::DELIVERY_STORE ||

$this->delivery === self::DELIVERY_STORE_ONLINE

) {

return self::DELIVERY_TYPE_STORE;

}

return self::DELIVERY_TYPE_NOT_SET;

}

public function getPaymentType()

{

if (

$this->delivery === self::DELIVERY_STORE_ONLINE ||

$this->delivery === self::DELIVERY_COURIER_ONLINE

) {

return self::PAYMENT_TYPE_ONLINE;

}

if (

$this->delivery === self::DELIVERY_STORE ||

$this->delivery === self::DELIVERY_COURIER

) {

return self::PAYMENT_TYPE_CASH;

}

return self::PAYMENT_TYPE_NOT_SET;

}

}

When the data and load grows, we will realize how badly this mixed column is impacting some queries performance. If we decide to make the big change and split it in separate columns, it would require changing one, maybe few source files. If this mixed concept is handled whenever needed in the code, it would be a significant undertaking, which often discourages refactoring the data model.

Map related columns to related properties (merging)

To satisfy some particular queries performance, a users table had email addresses split into two columns: username and domain, something like

| id | username | domain |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | user1 | gmail.com |

| 2 | user2 | yahoo.com |

| 3 | user3 | example.com |

We can map both columns to be accessed using a single getter and setter

class User

{

/** @ORM\Column(type="string") */

private $username;

/** @ORM\Column(type="string") */

private $domain;

public function getEmail(): string

{

return $this->username . '@' . $this->domain;

}

public function setEmail(string $email)

{

$parts = explode('@', $email);

$this->username = $parts[0];

$this->domain = $parts[1];

}

}

If we might need only username or domain data in some places, we can add specific accessors for them as well.

Another example was designed when the used RDBMS imposed hard limits on text column size. The product table ended up with description1 and description2 columns, and concatenation was carried out as needed. However each contributor implemented his own concatenation.

$description = $description1 . $description2;

$description = sprintf('%s%s', $description1, $description2);

$description = $description1;

if (!empty($description2)) {

$description .= $description2;

}

$description = $description1 . $description1;

The last one is my favorite, an example of a bug that shows up only with specific datasets. Corner cases are easily missed during testing.

Some other common examples include dates and times split in separate columns (year, month, day) and other combinations.

Map related columns to related properties (composition)

Sometimes there is a group of columns within a table which are related and often used together.

As an example, consider this orders table

| id | state | date | customer_id | … | delivery_date | delivery_address | delivery_status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hint: sometimes the related columns use the same name prefix. In this situation we can map the delivery columns as a composed class, as if it was a One-To-One relation. We can achieve this using Doctrine’s Embeddables

/** @ORM\Entity */

class Order

{

/** @ORM\Id */

private $id;

/** @ORM\Column(type = "integer") */

private $state;

/** @ORM\Column(type = "datetime") */

private $date;

/** @ORM\Embedded(class = "Delivery") */

private $delivery;

}

/** @ORM\Embeddable */

class Delivery

{

/** @ORM\Column(type = "datetime") */

private $date;

/** @ORM\Column(type = "string") */

private $address;

/** @ORM\Column(type = "integer") */

private $status;

}

Map related columns to related properties (inheritance)

In some cases it doesn’t make sense to extract some related columns using composition.

Consider the following orders table

| id | state | date | … | canceled | cancel_date | cancel_reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

There are 3 columns holding cancellation data. We could embed a Cancellation class within an order, but that wouldn’t make much sense. I can’t imagine a method getting a Cancellation object as an argument. The second hint about this transformation is that only a subset of the data has those columns set. We can map such a table using single table inheritance

/**

* @ORM\Entity

* @ORM\InheritanceType("SINGLE_TABLE")

* @ORM\DiscriminatorColumn(name="cancelled", type="boolean")

* @ORM\DiscriminatorMap({"true" = "CancelledOrder", "false" = "Order"})

*/

class Order

{

}

/**

* @ORM\Entity

*/

class CancelledOrder extends Order

{

/** @ORM\Column(type = "datetime") */

private $cancelDate;

/** @ORM\Column(type = "string") */

private $cancelReason;

}